Important Note: I am not a therapist. Nothing in this post is a substitute for professional therapy or advice.

Grief can be debilitating. Hopefully, by providing you with some background on grief, what it is, and how it can affect us, it can become just a tiny bit less debilitating.

The image of grief that comes to mind for many is of a romance movie where two star-crossed lovers fall in love, one tragically dies, and the other has an intensely emotional reaction before finally “moving on” while cherishing the memory of their beloved. I don’t mean to minimize stories such as this, but grief is much more complex.

In reality, grief can be caused by many events other than the death of a loved one. Many reading this are probably going through a cancer journey. If you have been recently diagnosed, you are probably grieving the potential or actual loss of hopes and dreams you had. If your spouse has cancer, you could be grieving both for what he or she has to go through, and the loss of your own future with him or her.

But yes, the grief after your beloved dies is crushing.

I wrote a post about a year ago about what the first couple months of grieving was like. In it I wrote that, for me, there were four aspects, or experiences, of grief and loss. The first was the feeling of losing a purpose in your life (i.e. husband of Julia); the second is the experience of losing the activities you did together; the third is the experience of losing the hopes and dreams you had with your loved one; and the fourth is the most significant — the feeling of losing an actual piece of who you are. I still feel as if these are my main experiences of grief.

In reading and talking to people I’ve found that these are indeed common and universal feelings during grief. However, what is not so agreed upon is the more macro question of how people move through the grief process. I’ve looked into different theories of the grief process and I think they are worth looking at one by one. I don’t think any of them are perfect (how could a theory contain all the complexities of grief?), but they all contain some truth about grief that is helpful to think about.

Attachment theory is one of the most prominent theories in many topics in psychology, especially grief. In it, John Bowlby asserts that there are four phases of mourning after a loss: Numbing, Yearning and Searching, Disorganization, and Re-organization. Numbing is the initial stage of disbelief and the inability to feel much. Yearning and searching is characterized by constant thoughts of the lost person and severe pain. Disorganization is the confusion and despair after it finally settles in that the loss is permanent. Then there is re-organization, where things start to turn for the better as painful thoughts slowly recede and happier memories take their place.

This is an interesting theory, but the stages weren’t in the same order for me. The first two stages were actually flipped for me — I initially felt very deep emotional pain and couldn’t stop thinking about Julia’s death, especially her state in the final days and hours. That soon turned into a lot of numbness and a sense of how bizarre everything was.

A theory that is very similar to attachment theory is Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief. The five stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

Another prominent theory of grief is Worden’s tasks of mourning. Moving through these tasks will, according to Worden, eventually produce “equilibirum” in the mourning individual. The tasks are: accepting the loss, working through the pain of grief, adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is missing, and finally, moving on to your new life without the person.

All of these theories are slightly over-generalized from my view — I believe that all of these feelings blend together at various points. There aren’t necessarily neat stages or tasks to separate them into. Two of the theories that match my experience best are Silverman and Klass’s continuing bonds, and Streobe and Schut’s dual process.

Continuing bonds may sound like you are supposed to forget that your loved oneshave died, maybe have some visions of them, talk to them about your grocery lists, etc. However, it just means that you will always have some sort of relationship with the person after his or her death – and you should!

But there is no single way to continue this bond; it can manifest itself in anything from using a favourite phrase of the loved one in your daily life, to looking at pictures, to sharing memories at the dinner table, to taking up a cause the person stood for. The point is that, unlike some of what the other theories seem to argue, you never have “closure” or “move on”. You learn to incorporate the person into your life in a way that doesn’t deny his or her death, but also doesn’t deny that he or she is still an important part of your life.

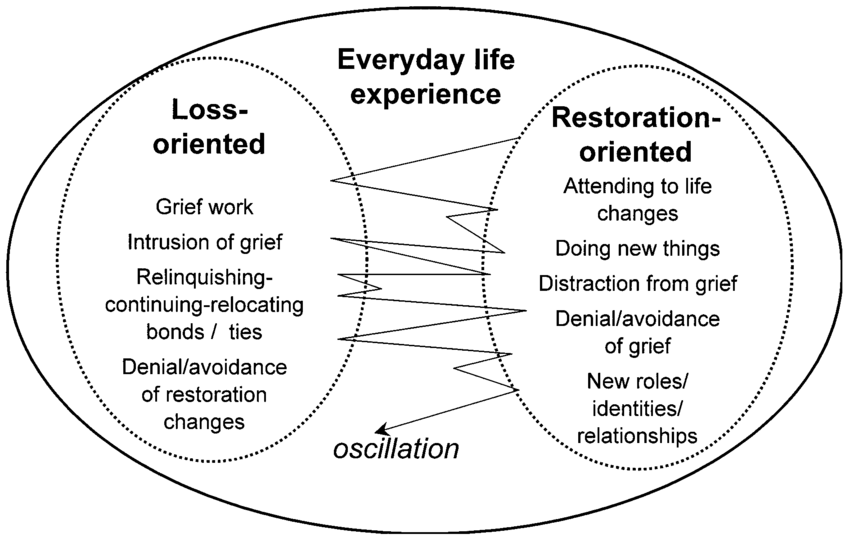

The dual process model (DPM) of grief is a response to the so-called “grief work” theories described above, where there are stages or tasks one must force oneself through in order to find “closure”. The developers of the theory, Stroebe and Schut, think that it is not always healthy to embrace the negative feelings of grief, and that breaks from grief are important. They would still say it is inevitable that the grieving person will have to go through periods of intense emotion and feelings of loss, but that it is good to focus on restoration throughout the grieving process.

In DPM, there are two types of stressors from grief: loss-oriented stressors and restoration-oriented stressors. Loss-oriented stressors arise when the griever is focusing on the loss of the person through strong memories, looking at photos, imagining the voice speaking into a situation, etc. Restoration-oriented stressors don’t necessarily come about when focusing on the lost person, but are a result of trying to find a “new normal” after the loss. Feeling lonely, having to cook for one instead of two, having to slip alone into a cold bed – these are all restoration-oriented stressors.

My understanding of this theory is that you will always have negative emotions from the feelings of loss, but you can move through the restoration part so that eventually you don’t always have to carry this negative mood towards daily tasks. You will always oscillate between feeling loss and feeling restoration, you will never be able to focus on just one or the other. But that’s ok. Eventually, these restoration-oriented stressors will dissipate and life will be easier, even if you’ll continue to struggle through feelings of loss.

I’ve gone through a large amount of theory in this post, and I commend you for not falling asleep yet. This exercise helped me because it confirmed for me that my experience with grief is relatively “normal”. Although I don’t identify with some of the above theories as much as others, there are parts of each theory that I can relate to. The biggest takeaway for me is that grief manifests itself differently at different times and situations. It’s important to get in touch with how your grief is presenting itself at a given time, whether it’s through prayer, meditation, counselling, or whatever else works. Have compassion on yourself if your grief is a heavy burden and you just need rest. But it’s also important to maintain a healthy lifestyle – exercise, meet up with friends, experience nature, eat well – because this will make the burden a little bit lighter.

Everyone experiences grief differently and there is no “right answer” for how to progress through the grief journey. What’s important is that you figure out how you are experiencing it, and do what you need to do to, not move on, but move forward.